|

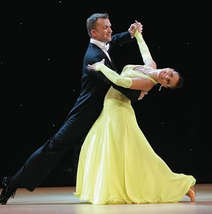

By: Anonymous When I first started doing RPM, it was much easier to follow an experienced teacher, someone who had worked with a lot of students with different abilities and had a better understanding of my anxieties and strange body movements, a teacher who could figure out the most appropriate prompts and encouragements that would work for a learner like me. It was a novel thing, learning how to simultaneously integrate auditory, visual, kinesthetic and tactile information and consistently output a coordinated muscle response. Even after I became quite comfortable working with a teacher, it was not easy to transfer my abilities to someone new, since I was quite awkward and anxious, and would immediately tense up and lose motor control, trying to process the subtle and not so subtle differences in prompts. As my own skills improved, I got much better at working with different leads, but it is still a struggle to follow someone who has not sufficiently developed their own skills. Forgive me for misleading you…that last paragraph was actually about what it was like for me during the year I learned how to ballroom dance as a frustrated science graduate student. In many ways, RPM is much like a dance between two people, the leader and the learner. When RPM is fluent, the coordination between leader and learner flows smoothly with its own dynamic rhythm. The best practitioners make RPM look easy. They have a tremendous skill set, and can find ways to connect with even the most recalcitrant students. The trouble with the ballroom dancing analogy is that my neurotypical brain is considerably more efficient at integrating and processing sensory information than an autistic brain. I can usually focus simultaneously on multiple sensory modes without concentrating, and my physical body (more often than not) acknowledges and responds to my mind with good coordination of words, gestures, and actions. The issues I struggled with during my short-lived dance career were insignificant compared to those of an autistic student. The autistic student must not only interpret real-time sensory information that is often fragmented or overwhelming, but she may also lack the motor coordination to physically (and/or verbally) respond in the appropriate way. Moreover, the same student may lack the motor control to resist an inappropriate physical or verbal impulse despite her frustrated desire to suppress such impulses. Both medicine and therapy have failed the autistic population for 50 years based on this egregious lack of understanding-that severe autism involves impaired sensory and motor integration, not impaired thinking. RPM is an extremely flexible teaching method capable of targeting the unique sensory system and motor abilities of the individual learner. RPM is not a cure or a one-size-fits-all therapy designed to mold autistic behavior towards a desired optimum. RPM assumes only that the student, no matter her education level or physical disability, is fully competent to learn. Because learning never stops, there is no limit to what can be taught or achieved in RPM. This is only one of the many ways that the goals of RPM differ from the goals of other autism therapies that aim to help the student “be more normal”. Unlike most other therapies designed to promote communication, the considerable flexibility built into RPM places an unusually high demand on the teacher. Although RPM assumes the student is fully competent to learn, no such assumption is made that the teacher is competent to teach. To become successful at teaching RPM is as difficult as it is rewarding. This is reflected in the scarcity of qualified RPM providers. The handful of HALO-recommended providers have undergone rigorous years-long training and apprenticeships to acquire skills that enable them to work with students of all abilities. For newcomers to RPM, it can seem daunting to navigate the road to unlock your child’s true abilities and intellect. It can take weeks, months, and even years to achieve open communication. So for those of us who are new to RPM, watching a skilled practitioner connect with a child can be a truly extraordinary experience, and extremely frustrating when we are slow to achieve similar success at home. This brings me to a fundamentally wrong-headed assumption that fuels a lot of unnecessary controversy regarding the validity of RPM as a teaching and communication method:

If an autistic student demonstrates proficiency at RPM with her teacher, she should be able to do it with anyone, right? I hope it is clear by now why this is patently false. Even with my neurotypical sensory integration and motor ability, dancing with an unfamiliar partner requires adjusting to his alternate prompts, disrupting the motor feedback pathways I rely on to follow his lead. This triggers anxiety, accompanied by loss of coordination and many apologies for stepping on feet. For both leader and learner, it takes practice with many different partners to seamlessly generalize skills to a novel partner. While the challenge of generalizing skills may be obvious in the context of ballroom dancing, a bewildering majority of trained autism therapists and professionals cannot wrap their head around the idea that a learned skill may not easily generalize from one therapist or environment to another. For those of you who eagerly await validation of RPM as a research-based method, please keep in mind that current testing paradigms often ignore this very real challenge to autistic learners. An inappropriate testing environment prevents the autistic student from revealing her true ability and aptitude. In contrast, when special education pioneers begin to acknowledge correlations between performance, anxiety, and familiarity with the therapist and environment, this will surely lead to better and more creative testing paradigms that will establish RPM as a valid teaching method and will not only help advance the field of special education, but of education in general. NOTE: The author is a research faculty Ph.D. in neuro-opthalmology who studies diseases of the visual system.

Violet Jones

6/14/2016 09:13:38 am

This is such an excellent article on explaining the importance of a competent teacher in RPM. Through the guidance of Lenae Crandall, my son learned to communicate his knowledge fluently. However, it took longer to generalize this skill to his parent, (me), and still longer to generalize this skill to others. So many elements come into play, including my son's anxiety, and the novel person's way of prompting, and fading prompts. Once thing I have learned through years of another therapy is that my son does not generalize skills easily, but rather, must learn each skill in different situations, and with different people in order to be completely independent. If we remember that this is typical of learning new skills in autism, it makes complete sense that RPM must be generalized to each person and situation. Furthermore, I have read criticism that the student is responding to prompts, and thus not really communicating. I would respond that, as in other therapies, prompts are faded as the skill becomes more independent. The minimal level of prompt is always used. Through this method, my son learned to type independently on a keyboard which is on his lap or on a table. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorLenae Crandall Archives

March 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed